The annual Rencontres d'Arles photography festival, long revered as a sacred gathering for the custodians of the lens and the silver halide print, has boldly pivoted its gaze this year. In a move that has sent ripples through the traditional art world, the festival’s latest edition has placed Artificial Intelligence-generated imagery at the very heart of its sprawling exhibition program. This is not a side show or a speculative footnote; it is a central, provocative thesis on the future of image-making itself.

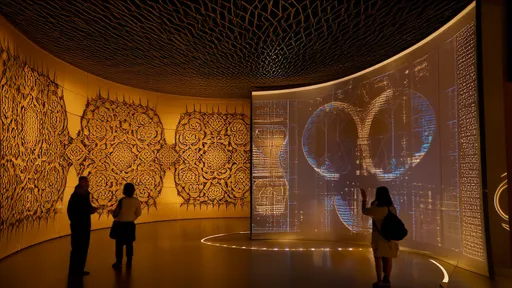

Nestled in the sun-drenched, ancient Roman town of Arles in the South of France, the festival has historically been a temple to photographic purity. It is a place where the ghosts of Cartier-Bresson and Doisneau seem to linger in the cobblestone streets. To witness this institution embrace AI, a technology often viewed with skepticism and outright hostility by artistic purists, is to witness a profound cultural shift. The curators have not merely dipped a toe into these digital waters; they have plunged in headfirst, presenting a wide array of works that explore, critique, and celebrate the creative potential of algorithms and neural networks.

The exhibited works are far from the sterile, often derivative outputs one might associate with early AI art. Instead, they showcase a staggering range of aesthetic sensibilities and conceptual depths. One featured artist, a collective known as Obvious, whose AI-generated portrait once fetched a contentious sum at Christie’s, presents a new series that interrogates the very notion of authorship and the "ghost in the machine." Their images, hauntingly reminiscent of 18th-century portraiture yet eerily alien, force viewers to question where the artist's intent ends and the machine's stochastic process begins.

Another compelling installation comes from an artist who trained a generative adversarial network on a decades-long archive of satellite imagery. The resulting pieces are vast, breathtakingly detailed landscapes of a world that never was—coastlines that defy known geography, city grids that sprawl in impossible fractal patterns. These are not just pretty pictures; they are potent commentaries on climate change, urbanism, and the datafication of our planet. The artist uses the AI not as a crutch but as a collaborator, a tool to visualize futures and alternatives that lie beyond the limits of human imagination or traditional photography.

Perhaps the most debated section of the festival is a curated show titled The Synthetic Gaze. This exhibition-within-an-exhibition directly confronts the ethical quagmires that AI image generation brings to the fore. It features projects that use AI to resurrect historical figures, generate photojournalistic images of events that never occurred, and create intimate family portraits of entirely fictional subjects. The power of these works lies in their uncomfortable verisimilitude; they look real, they feel real, and that is precisely what makes them so deeply disconcerting. They challenge our foundational trust in the photograph as a document of reality, a trust that has already been severely eroded in the digital age.

The festival’s programming extends beyond the gallery walls, fostering a crucial dialogue around this technological revolution. Daily symposiums feature not only artists but also leading computer scientists, philosophers, and critics. The conversations are heated, passionate, and essential. Topics range from the technical intricacies of diffusion models and transformer architectures to profound philosophical debates about creativity, consciousness, and the soul of art. One philosopher argued that AI art is the ultimate culmination of the readymade, a Duchampian gesture executed by a machine, while a neuroscientist presented on how the human brain responds to AI-generated imagery with the same patterns of engagement as it does to human-made art.

Unsurprisingly, this curatorial direction has not been met with universal acclaim. A vocal contingent of traditional photographers and critics have decried the move, labeling it a capitulation to tech trends and a betrayal of the festival's photographic roots. They argue that the hand of the artist, the intentionality of the click, the alchemy of the darkroom, and the unique relationship between a photographer and their subject are being sidelined for the cold, calculated outputs of silicon and code. Their protests, however, seem to only fuel the discourse, making the festival grounds a vibrant battlefield of ideas.

What the Rencontres d'Arles has masterfully achieved is the legitimization of AI-generated imagery as a serious, complex, and urgent medium within the contemporary art landscape. By providing a prestigious platform for these works, the festival is not declaring the death of photography but rather heralding its explosive evolution. It posits that the camera is no longer the sole gatekeeper of the image. In its place, a new ecosystem is blooming—one where code, data, and human curiosity intertwine to create new forms of visual storytelling.

The message from Arles is clear: the future of the image is synthetic, hybrid, and fiercely debated. This year’s festival will be remembered not for a single iconic photograph, but for launching a thousand questions. It has successfully framed AI not as a threat to be feared, but as a formidable, bewildering, and ultimately creative force that is now an indelible part of our cultural fabric. The conversation has moved from if this is art to what kind of art it will be, and who gets to decide.

By /Sep 11, 2025

By /Sep 11, 2025

By /Sep 11, 2025

By /Sep 11, 2025

By /Sep 11, 2025

By /Sep 11, 2025

By /Sep 11, 2025

By /Sep 11, 2025

By /Sep 11, 2025

By /Sep 11, 2025

By /Sep 11, 2025

By /Sep 11, 2025

By /Sep 11, 2025

By /Sep 11, 2025

By /Sep 11, 2025

By /Sep 11, 2025

By /Sep 11, 2025

By /Sep 11, 2025

By /Sep 11, 2025

By /Sep 11, 2025