In a landmark move for art historians and cultural researchers worldwide, the Documenta Archives have unveiled their digital repository of East German avant-garde art. This unprecedented release opens a portal to one of the most politically complex and artistically rich periods in modern German history, offering over 10,000 digitized works, sketches, letters, and exhibition catalogs that were previously inaccessible to the public. For decades, these artifacts were confined to physical storage, known only to a handful of scholars and curators. Their digital liberation not only democratizes access but also recontextualizes a movement that operated under the shadow of state surveillance and ideological pressure.

The collection spans from the late 1960s to the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, capturing the evolution of experimental art in the German Democratic Republic. Unlike state-sanctioned socialist realism, which dominated official galleries, the avant-garde scene thrived in private apartments, church basements, and clandestine studios. Artists like A.R. Penck, Gerhard Richter (in his early East German years), and lesser-known but equally radical figures such as Cornelia Schleime and Via Lewandowsky pushed boundaries through abstract painting, performance art, and subversive installations. Their work often critiqued the regime's oppressive policies, using metaphor and ambiguity to evade censorship. The digital archive includes high-resolution scans of paintings, photographs of ephemeral performances, and even audio recordings of artist discussions, providing a multidimensional view of this underground ecosystem.

What sets this archive apart is its meticulous curation of contextual materials. Beyond the artworks themselves, researchers can access Stasi files related to surveillance of artists, personal diaries detailing creative struggles, and exhibition invitations printed secretly on makeshift presses. These documents reveal the constant tension between creation and suppression. For instance, correspondence between artists shows coded language used to organize shows, while state reports expose the paranoia of cultural authorities who viewed abstraction as and . This duality makes the archive not just an art historical resource but a socio-political testament to resilience.

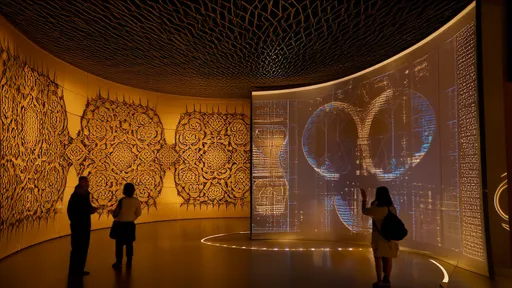

The technological effort behind the digitization was herculean. Many works were fragile—fading photographs, crumbling paper, or unstable mixed-media pieces—requiring specialized equipment and conservators. Metadata was painstakingly compiled from scattered sources, including surviving artists' testimonies and archived exhibition logs. The result is a searchable platform that allows users to explore by artist, medium, date, or even thematic tags like or Interactive features let viewers zoom into brushstrokes or compare drafts of a single work, revealing artistic processes hidden for generations.

Scholars hail the release as a game-changer. Dr. Elena Fischer, a historian of Cold War art, noted, The timing is also symbolic; as Germany grapples with renewed debates over historical memory, this project underscores the importance of preserving marginalized narratives. Educational institutions already plan to integrate the database into curricula, while museums may rethink exhibitions on 20th-century European art.

However, the archive raises ethical questions. Some documents involve informants who betrayed artists, and living relatives may be implicated. The Documenta team worked with ethical consultants to anonymize sensitive personal data while maintaining historical accuracy. Additionally, copyright issues were navigated with heirs and surviving artists, ensuring fair representation.

For the global public, the archive is freely accessible online, breaking geographical barriers. A farmer in Brazil can now study the brushwork of an East German dissident, or a student in Korea can analyze protest performances. This aligns with a broader trend in cultural institutions to decolonize archives and promote transnational dialogue.

In essence, the Documenta Archives have not merely digitized art; they have resurrected a silenced conversation. This project invites us to reconsider Cold War cultural maps, where East German avant-garde art was often overshadowed by Western movements. Now, it claims its rightful place in global modernism, vibrant and unignorable. As users click through its digital corridors, they engage in an act of historical recovery—one that celebrates art's power to endure beyond politics and time.

By /Sep 11, 2025

By /Sep 11, 2025

By /Sep 11, 2025

By /Sep 11, 2025

By /Sep 11, 2025

By /Sep 11, 2025

By /Sep 11, 2025

By /Sep 11, 2025

By /Sep 11, 2025

By /Sep 11, 2025

By /Sep 11, 2025

By /Sep 11, 2025

By /Sep 11, 2025

By /Sep 11, 2025

By /Sep 11, 2025

By /Sep 11, 2025

By /Sep 11, 2025

By /Sep 11, 2025

By /Sep 11, 2025

By /Sep 11, 2025